10.18.22

Fighting Plastic Pollution Across the Globe: Surfrider Presents at International Conference

By Surfrider HumboldtYou know a conference has been successful when you leave informed, inspired and with a greater sense of connectivity. The 7th International Marine Debris Conference held in Busan, Republic of Korea last month achieved exactly that. Activists, educators, scientists and industry players from all over the planet joined together to explore the problem of – and potential solutions to – plastic pollution.

Northeast Regional Manager Melissa Gates, Plastic Pollution Initiative Senior Manager Jennifer Savage and Surfrider Kaua`i chapter volunteers Cynthia Welti and Carl Berg represented Surfrider Foundation over the course of the conference through presentations and posters highlighting regional success stories and our national plastic pollution reduction efforts.

Collectively, the presentations, posters and associated events affirmed that plastic production and pollution are absolutely global problems that will require global solutions including stopping the manufacture of single-use plastic items and seeking alternatives to plastic wherever possible. Plastic production not only results in our planet being blanketed by plastic waste, but emits massive amounts of greenhouse gasses into the world and is poisoning people and wildlife throughout the world.

Surfrider Foundation’s Plastic Pollution Initiative team, along with our extensive chapter and club network, are all working together to encourage government, industry and individuals to protect our ocean, waves and beaches by moving away from unnecessary single-use plastics. Attending and presenting at 7IMDC provided us a chance to share our victories and lean into new opportunities to make a difference at home and around the world. You can support these efforts by donating today!

Brief descriptions of our presentations and posters at 7IMDC are below.

The United States’ Role and Responsibility in Stopping Ocean Plastics

This session, co-chaired by Gates and the Ocean Conservancy’s Nicholas Mallos began with the Sea Education Association presenting scientific research showing that the United States generates the most plastic waste of any country.

This U.S. pollution contribution persists despite increased public awareness, underscoring the need for new policies focused on industry responsibility. To showcase our success in pushing for those changes, Savage presented Surfrider’s newly updated policy map, an interactive tool documenting more than 1,000 plastic pollution-related laws and ordinances. Our experience shows that passing multiple local laws often prompts new statewide efforts. As more states move to stop plastic pollution at the source, we create the momentum needed to achieve systemic change through federal legislation.

While many of the initial laws focused only on a single type of item (i.e., bags, balloons, straws), new legislation trends toward covering multiple products and holding manufacturers more accountable. Gates used Maine’s 2021 Extended Producer Responsibility for packaging law and the recently passed SB 54 in California as examples, emphasizing the imperative for intersectional, comprehensive solutions that result in a shift away from single-use and advance environmental justice while stopping plastic pollution at the source.

In whole, this session confirmed that the U.S. must take bold action to ensure we are not a leading contributor to the global plastic pollution problem, but rather a leader in advancing real solutions.

Providing a Framework for Plastic-Free Restaurants

This session featured presentations from representatives of Oceanic Global, 5Gyres, Clean Water Fund, Ponguinguiola and Plastic Free Southeast Asia, and included a presentation on Surfrider’s Ocean Friendly Restaurant guidelines and successes, and our goal of expanding the Ocean Friendly program to incorporate additional industries.

Presentations highlighted volunteer programs designed to support and encourage businesses in transitioning away from single-use plastics to a more sustainable system of reuse. All presenters agreed on the importance of these efforts being driven by the local community, as well as the imperative to find ongoing means of support.

Volunteer Cleanups during the Era of COVID-19

In this session, Savage showcased how Surfrider’s Beach Cleanup program, run by Healthy Beaches Manager Jenny Hart, adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges to cleanup efforts included beach closures, limits on gatherings and the addition of new commonly found items. In response to this, protocols for solo cleanups were developed and Surfrider’s cleanup database was opened to the public. This allowed for greater diversity in cleanup locations and empowered individuals to report their findings. As a result of the adaptability and resilience shown during 2020, 8,895 Surfrider volunteers held 927 beach cleanups and removed over 80,000 pounds of trash and recycling from our beaches, neighborhoods and waterways.

A decline in marine debris abundance on Hawaiian shores?

Kaua`i Chapter Staff Scientist Carl Berg presented a study documenting marine debris on Hawaiian shorelines. Surfrider Foundation coordinated community beach cleanups and weekly targeted net patrols on Kaua`i to collect and report tonnage of marine debris removed from windward shores from 2013 to 2021. The greatest mass of debris collected (71%) was Abandoned, Lost or Discarded Fishing Gear (“ALDFG”; i.e., fishing nets, ropes, hard plastic buoys) that was sourced at sea and not land-based trash. From a peak of 17.5 tons collected in Q2-2018, quarterly yields decreased to 4.7 tons in Q4 -2021.

Meanwhile, Hawai`i Wildlife Fund conducted community-based cleanups and net patrols on the southeastern shores of Hawai`i Island since 2003. Quantitative surveys from 2016 – 2021 report the number of marine debris items collected during standardized NOAA Marine Debris Monitoring and Assessment Project 100m transects (N= 50 surveys). There was a marked decline from ,6916 pieces in August 2018 to 594 in October 2021.

Together, these different datasets demonstrate a major decline in marine debris abundance or distribution is occurring within the North Pacific Ocean, likely due to the shift of the “garbage patch” northeast and farther from the Hawaiian Islands. Results using new data and a refined model will be presented in the future.

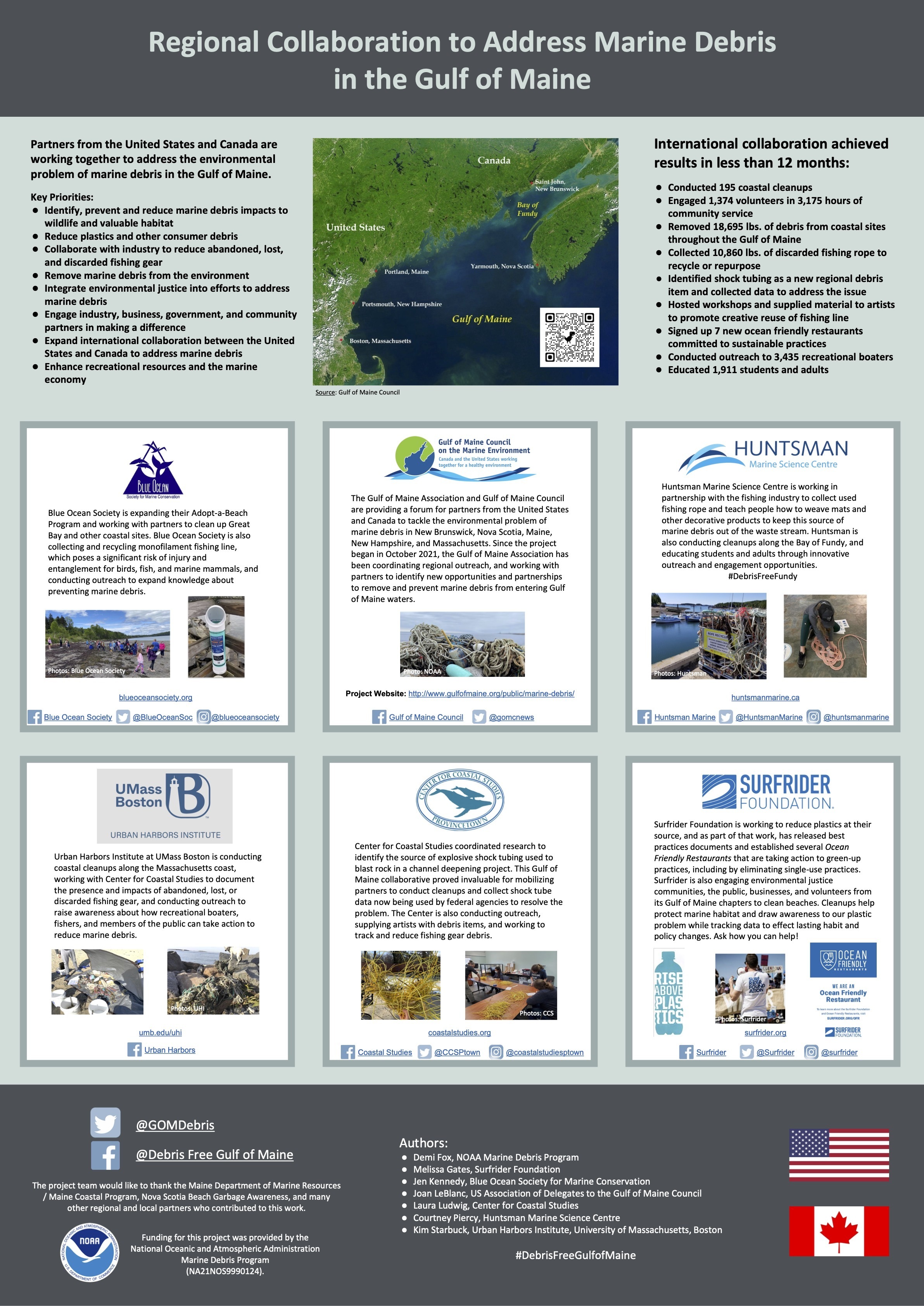

Regional Collaboration to Address Marine Debris in the Gulf of Maine – poster session

In November 2021, a new collaboration was created to address the environmental problem of marine debris in the Gulf of Maine. State and federal government representatives, non-profit organizations, volunteers, and academic partners from the US and Canada are working across the five jurisdictions bordering the Gulf of Maine (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts) via this international collaborative approach to reduce plastic and other marine debris in the Gulf of Maine watershed.

Over the past six months, the team has conducted 105 coastal cleanups, engaged 720 volunteers, and removed 7,774 pounds of debris from coastal sites. An additional 5,500 pounds of discarded fishing related rope was collected and workshops were hosted to promote creative reuse and keep these materials out of the waste stream. The team has also engaged more than 3,500 students and adults in learning about the negative impacts of marine debris on the environment and actions to make a difference. The team is collaborating with industry to reduce plastics at their source and has already designated several ocean friendly restaurants for their commitment to reducing plastics.

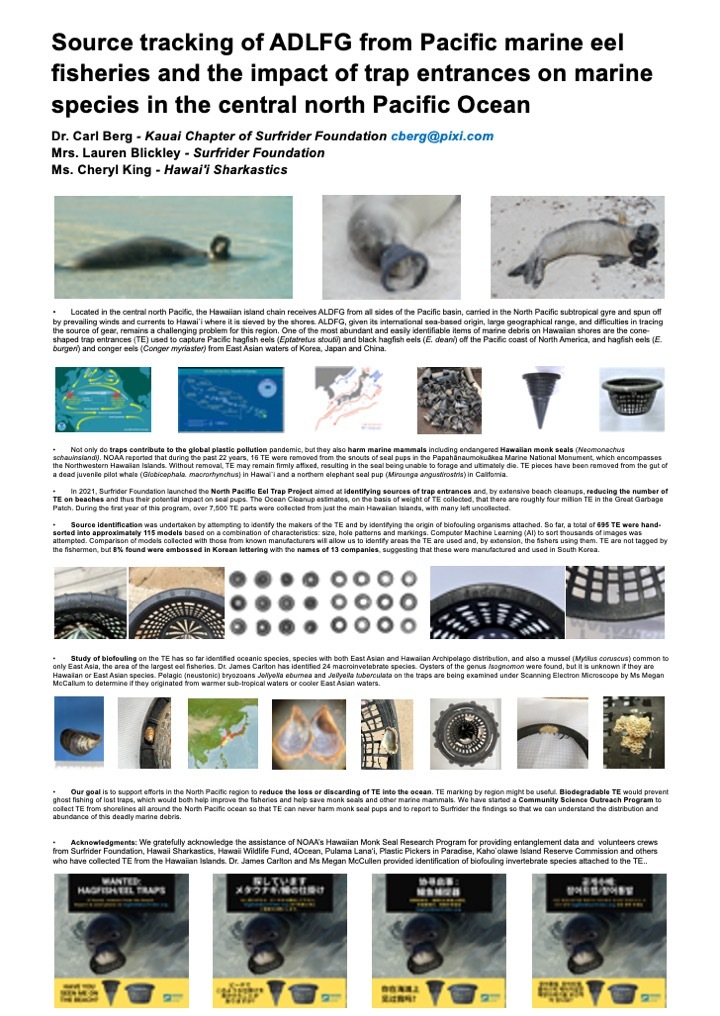

Source tracking of ADLFG from Pacific marine eel fisheries and the impact of trap entrances on marine species in the central north Pacific Ocean – poster session

The Kaua’i chapter Hawaiian island chain receives ALDFG from all sides of the Pacific basin, carried in the North Pacific subtropical gyre and spun off by prevailing winds and currents to Hawai`i where it is sieved by the shores. ALDFG, given its international sea-based origin, large geographical range, and difficulties in tracing the source of gear, remains a challenging problem for this region.

Not only do traps contribute to the global plastic pollution pandemic, but they are also responsible for harming marine mammals including endangered Hawaiian monk seals. NOAA reported that during the past 22 years, 16 TE were removed from the snouts of seal pups in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, which encompasses the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Without removal, TE may remain firmly affixed, resulting in the seal being unable to forage and ultimately die. TE pieces have been removed from a dead juvenile pilot whale in Hawaii and a northern elephant seal pup in California.

In 2021, Surfrider Foundation launched the North Pacific Eel Trap project aimed at identifying sources of the TE and, by extensive beach cleanups, reducing the number of TE on beaches and thus their potential impact on seal pups.

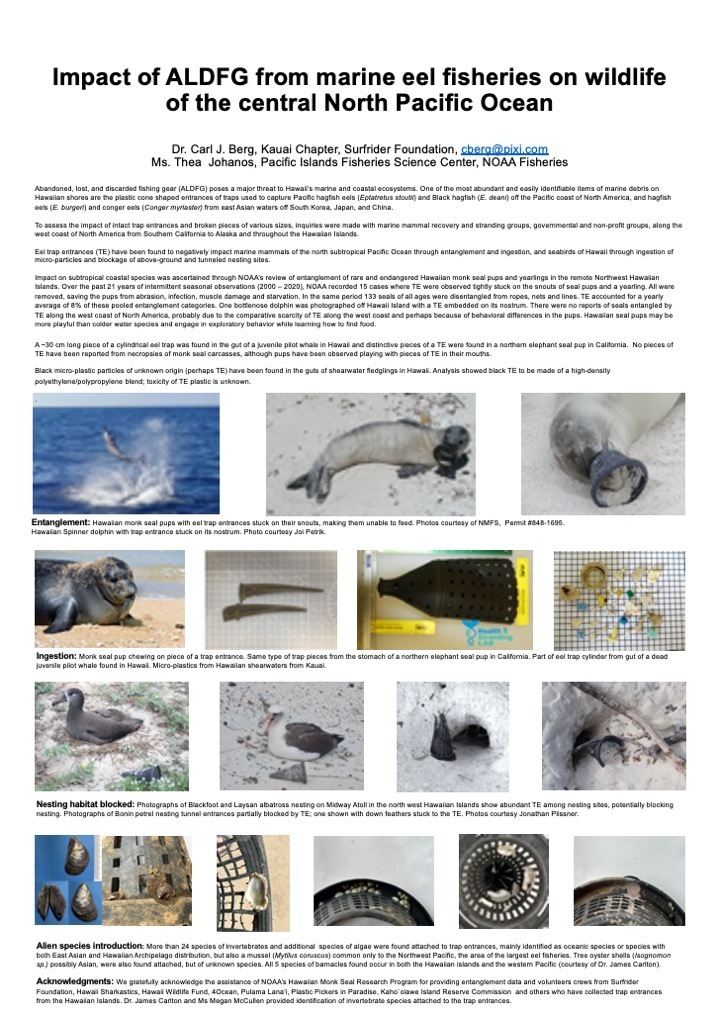

Impact of ALDFG from marine eel fisheries on wildlife of the central North Pacific Ocean – poster session

Abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) poses a major threat to the marine and coastal ecosystems of Hawai’i. One of the most abundant and easily identifiable items of marine debris on Hawaiian shores are the plastic cone shaped entrances of traps used to capture Pacific hagfish eels (Eptatretus stoutii) and Black hagfish (E. deani) off the Pacific coast of North America, and hagfish eels (E. burgeri) and conger eels (Conger myriaster) from east Asian waters off South Korea, Japan, and China.

To assess the impact of intact trap entrances and broken pieces of various sizes, inquiries were made with marine mammal recovery and stranding groups, governmental and non-profit groups, along the west coast of North America from Southern California to Alaska and throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

Eel trap entrances (TE) have been found to negatively impact marine mammals of the north subtropical Pacific Ocean through entanglement and ingestion, and seabirds of Hawaii through ingestion of black micro-particles and blockage of above-ground and tunneled nesting sites.

Reducing Derelict Fishing Gear in Hawaii Through Community Science and Trans-Pacific Partnerships – poster session

Lost and discarded fishing gear poses a major threat to Hawaii’s marine and coastal ecosystems. Yet given its international scope, large geographical range, and difficulties in tracing the source of gear, derelict fishing gear remains a challenging problem. One of the most abundant and easily identifiable items of marine litter on Hawaiian shores are the cone-shaped trap entrances (TE) used to capture Pacific hagfish eels and conger eels from the Pacific Northwest and East Asian waters off Korea, Japan, and China. TE are also responsible for harming marine mammals, notably endangered Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi).

In 2021, Surfrider Foundation launched the North Pacific Eel Trap project aimed at reducing the number of lost and discarded hagfish/eel traps and their impact on Hawaiian monk seals. Efforts focused on removing TE from beaches, and documenting the location and abundance of TE, especially on monk seal pupping grounds, and Using size, shape and other characteristics, each TE was assigned to a “model”. By identifying the maker of each model, we plan on identifying the fisheries where they are used.

A community outreach campaign, consisting of emails, social media, local newspapers, and television news was published throughout Hawaii and distributed to Surfrider Foundation volunteers, fishery managers, and nonprofit organizations along the West Coast of North America. Volunteers are directed to take photos and submit reports of TE to hagfish@surfrider.org. These reports are then recorded in a spreadsheet and a photograph database is maintained. We intend to use the 7th IMDC to expand outreach out to partners throughout the North Pacific region.

During the first year of this program, collaborating non-governmental organizations and community volunteers collected and reported over 7,500 TE parts from the main Hawaiian islands. We also received 15 TE from Kure Atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and photographs of TE from the West Coast of the United States. Through extensive community outreach and partnerships, the project has increased community awareness about ALDFG, removed thousands of TE from Hawaii beaches, and provided baseline data on TE abundance across the Hawaiian Islands. In addition, the data has enabled us to start categorizing TE and identifying TE sources.

Building on this data and successful collaborations, the project aims to ultimately support efforts in the North Pacific region to reduce the loss or discarding of TE into the ocean via improved gear design, harvesting methods, or TE marking. Representing one of the first trans-North Pacific partnerships between community organizations, fishers, and fishery managers to reduce derelict fishing gear pollution in the North Pacific, the project may also serve as a replicable model for future international efforts aimed at combining community science with fishing gear reduction.