Surfrider collaborated with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Our Radioactive Ocean program to test beach water at the San Onofre surf zone and outfall site for radioactive isotopes. Results came back higher than the ambient ocean level of California coastal waters impacted by Fukushima, yet well below drinking water limits. This study was made possible thanks to donations from community members across Southern California.

At a 2018 San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) Community Engagement Panel meeting, Surfrider learned about batch liquid radioactive effluent releases, legally allowed to be dumped offshore of San Onofre State Park, a popular and cherished beach, surfing destination, campground, and cultural site. Surfrider immediately took action to learn more about the releases, advocate for stronger public transparency and outreach, and conduct independent, third-party testing of water radiation levels to better understand exposure.

Radioactive Effluent Releases

Batch radioactive liquid effluent releases have occurred at SONGS since 1968, despite the plant closing in 2013, when the nuclear power plant was shut down. Southern California Edison representatives stated via email that from 2000 to 2011, the plant averaged 171 radioactive liquid effluent releases each year. While the effluent is highly treated before being released, the treatment and filtration are not completely effective, meaning not all radioactive isotopes are removed before effluent is discharged into the marine environment. Alarmingly, this is a common practice across the nation’s coastal nuclear power plants, which are regulated by the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

During San Onofre’s decommissioning, the frequency and size of releases have been greatly reduced, yet still take place as a way to “dispose” of radioactive liquid collected from contaminated places like certain facility HVAC systems. Next year, releases will also include drained spent fuel cooling pool water in preparation for the two onsite cooling pools’ upcoming dismantlement.

The History: Advocating for Public Transparency

In addition to the general concern about these intentional radioactive releases, Surfrider was extremely disappointed in the severe lack of public transparency and notification. Nuclear plant operators are required to conduct thorough testing of their radioactive effluent and report releases and concentration levels to the NRC, yet do so only after the fact in an annual report. The reports do not provide detail on individual releases, and instead just provide the summation of released radioactive isotopes and effluent volume cumulatively over the course of the year. This means the public had no opportunity to be aware of when these releases were occurring, and what radiation dose they might be exposed to while recreating in the vicinity of the outfall site, which is only 1.1 miles offshore of a very popular surf break.

This was unacceptable. Surfrider started conducting outreach to Southern California Edison, the plant’s majority owner and operator, and state regulators including the California State Lands Commission, to get public notification included as a committed condition in upcoming permits. After multiple conversations, Southern California Edison voluntarily agreed to provide 48-hour advance public notifications of future batch releases to allow beach goers and the community to be better informed about potential radiation exposures. Their advance public notification commitment was codified in their State Lands Commission decommissioning permit. It’s our understanding that this was the first time a nuclear plant in the United States committed to and provided routine advanced notification of liquid radioactive batch releases. Surfrider California monitored their notification website and helped disseminate notifications on social and website channels.

Beach Water Radiation Testing

Now that the coastal community had the ability to be aware of upcoming radioactive effluent releases and additional (albeit reportedly low) exposure during coastal recreation in the area, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Our Radioactive Ocean program shared an opportunity to conduct independent testing of beach water radiation levels. The Our Radioactive Ocean (ORO) program was developed by Dr. Ken Buesseler, an internationally-recognized expert on radionuclides in the marine environment, founder of the Center for Marine and Environmental Radioactivity (or CMER) at Woods Hole, and the lead for tracking marine radiation levels from Japan’s 2011 Fukushima radioactive contaminant release.

At ORO, Dr. Buesseler established a volunteer monitoring program where coastal community members can order sample kits and follow very clear and simple sampling methods to collect a sample of their local beach water to ship back to ORO’s lab. Researchers at ORO then process and test the samples for the presence and concentration of Cesium-137 and Cesium-134, radioactive byproducts of nuclear fission (a process used by nuclear generation facilities). These radioactive forms of cesium are not naturally occurring, but occur at low levels everywhere due to human sources, including atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in the 1950’s and 60’s, and the nuclear power industry. Learn more from The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

With this option in hand, Surfrider conducted a “before-, during-, after-release” study of ocean radiation levels offshore of San Onofre to test if effluent releases resulted in a measurable increase in radioactive isotopes (specifically Cesium-137 and 134) in the nearshore environment. Samples were pulled in the Surf Zone near the southern end of San Onofre State Beach to reflect likely exposure during surfing and coastal recreation. Samples were also taken at the surface near the ocean outfall 1.1 miles offshore, for a more direct measure. The “before” samples were meant to be baseline measures to compare with the “during” and “after” measurements.

Top: Surf zone sample collection. Bottom: Offshore outfall sample collection, made possible thanks to the generous volunteer time and boat trips provided by Dan Stetson. Images by Colleen Henn.

The baselines were pulled on February 24, 2021, yet Southern California Edison subsequently paused all releases for over a year, with the next release not occurring until April 2022. With this lag in testing, we were unable to assume that our “before” samples were reflective of the baseline levels at the time of the measured “during” release, collected on April 25, 2022 and “after” release sample, collected on April 27, 2022. Regardless, the results were added to the Woods Hole ORO Database which tracks ocean radiation levels over time.

The Results

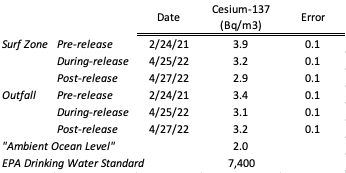

All six results had “below detection” levels of Cesium-134, meaning the concentration of that isotope was so low that it was immeasurable, even with the highly sensitive equipment used by Woods Hole. The Cesium-137 levels at all tested locations were higher than what’s considered to be the “ambient ocean concentration level” of 2 Bq/m3, with the before samples nearly double that amount. That said, double a very small amount, is still a very small amount. In fact, the “before” samples were the highest at 3.9 and 3.4 Bq/m3, which is still only a fraction of the nation’s drinking water limit for Cesium-137 (that’s right, this stuff is also legally allowed to be in drinking water at very low concentrations, set by the EPA at 200 pCi/L or 7,400 Bq/m3). Interestingly, the “during” release sample was lower than the “before sample”, at 3.1 and 3.2 Bq/m3. Finally, the “after” samples varied, with the outfall sample slightly increasing to 3.2 Bq/m3, and the surf zone sample decreasing to 2.9 Bq/m3.

Table 1. Results of beach water radiation sampling. Cesium-137 concentration results from each sampling event are provided alongside the “ambient ocean concentration level” and EPA’s drinking water limits for comparison.

So What Does This All Mean?

According to researchers at ORO, “there was not much difference between the before and after, and a decline since the pre-[release] samples in 2021. This would be consistent with the decay of Fukushima related Cs137.”

So did the SONGS release result in a measurable increase in the ambient Cesium-137 levels off San Onofre? Without an adequate baseline level to compare against- we can’t say. But two days after the April release, the level of cesium-137 in the surf zone decreased by 0.3 Bq/m3 (+/- 0.1 Bq/m3), while the level of Cesium-137 near the outfall was fairly constant, showing a very small increase- so small that it was within the error limit of the testing equipment (0.1 Bq/m3). Additional testing of future effluent releases would help clarify if a measurable increase (and subsequent decrease) in Cesium-137 levels occur in the coastal environment after a known SONGS radioactive effluent release. “Given variations in tides and upwelling along the California coast, such small differences cannot be attributed to any local sources” according to Dr. Buesseler. Further supporting this are similar levels found up and down the west coast in response to radioactivity released in 2011 from the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant disaster that ORO has been tracking.

Surfrider hopes to repeat this sampling effort to monitor ocean radiation levels at this popular coastal recreation site during upcoming batch releases of spent fuel cooling water, which are scheduled to take place in 2023.

Notes and Limitations

All samples were pulled from the ocean surface, even though the outfall and diffusers are located closer to the seafloor. Cesium-137 and 134 were the only radioactive isotopes analyzed during this study because those are the isotopes this specific Woods Hole ORO testing equipment is able to determine and quantify. It is possible that other radioactive isotopes are present in the beach water. This study did not test any beach sand or sea floor sediment for radioactive isotopes. Additional ocean processes could alter measurements of isotopes in the area, such as swell size and direction and current strength and direction, among others. This study is not attempting to determine if all of the Cesium-137 detected in the marine water surrounding San Onofre is due to a specific source, be it Fukushima Dai-ichi fall out, legacy radioactive military testing, SONGS or other potential sources. This effort is specifically looking to see if radioactive batch effluent releases are associated with a temporary yet elevated increase in immediate marine water Cesium-137 levels in the area.