In 2018, Surfrider learned that the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) has frequently been releasing radioactive effluent into the ocean, right next to one of the nation’s most beloved and popular surfing beaches, San Onofre State Park, for over 50 years. Needless to say, we were horrified. How much exposure have we had surfing there weekly, if not daily, for years? Is our health at risk? Is this even legal? When are these happening?

After interviewing expert Dr. Ken Buesseler to hear more about the risks (see full discussion below) we learned that while any additional radiation exposure is concerning, the amount reportedly released by Southern California Edison during liquid batch releases is 20 times lower than the level of radiation already in the ocean off California, which is 5,000 times lower than drinking water standards set by the World Health Organization. In other words, if you surfed San Onofre every single day for your entire life (100 years) your radiation exposure would still be one-tenth that of a single dental x-ray. So while the risk may be considered very low, we still believe you have the right to know about it.

2024 Update: Surfrider collaborated with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Our Radioactive Ocean Program to test beach water in the surf zone for levels of Cesium-137, a concerning radioactive isotope. Initial test results showed levels off of San Onofre were twice the ambient ocean concentration level, yet still well below drinking water limits. See results of all six testing efforts here. Please note that results do not represent the amount of radioactive isotopes from end of pipe (before ocean dilution), nor do they measure concentrations in other important areas like beach sand or biota.

To help ensure that surfers, beachgoers and the broader community could be informed, we made a plea to Southern California Edison (the plant’s majority owner and operator) to give the public advanced notification of these releases so we could at least be in the know and help moderate our potential exposure. Against all odds, Edison agreed to give these notices, making SONGS the first nuclear plant in the United States to provide advanced notifications of radioactive effluent releases. Granted, they only give a 48-hour notice and you have to log on to a quasi-buried page on their website to see the notification, but at least we could now know when these releases were happening.

Since then, Surfrider and other community groups have diligently tracked these batch release notices in order to keep the public informed. In the last few months, the frequency of these releases has gone up significantly, especially with SONGS ramping up their decommissioning efforts. But how dangerous are these releases?

At Surfrider, we believe people have the right to know about the status of their water quality, whether it’s the presence of fecal indicator bacteria (aka sewage!) or, sadly enough, radioactive materials in the beach water. But with this knowledge, we also need to have an understanding of what this exposure means and if we should be worried.

After dozens of inquiries from concerned community members about the actual risk and health impacts, we think it’s time we should all educate ourselves about this confusing and complex realm of radiological exposure in our environment. To help in this endeavor, we reached out to Dr. Ken Buesseler, a senior scientist at the prominent Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Dr. Buesseler is an expert when it comes to radionuclides in the marine environment, is the founder of the Center for Marine and Environmental Radioactivity (or CMER) at Woods Hole, and has been the international lead for tracking marine radiation levels from the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant disaster. He also started the Our Radioactive Ocean program where citizen scientists can collect water samples from their local beach, ship it to his lab at WHOI, and he will test for radioactive isotopes!

To help get some honest, independent answers regarding health impacts of SONGS liquid radiological effluent releases, Dr. Buesseler graciously offered to join me in an interview and share some valuable insights and expert analysis of Edison’s batch releases.

Q and A with Dr. Ken Buesseler about risks from irradiated water at San Onofre

1. In your professional opinion, do these releases at current dose levels pose a health threat to local beachgoers and surfers?

No. But I do share their concern. One way to look at this, is to consider how much radioactivity is being released, relative to what is already in the ocean. Most people don’t realize it, but the ocean already contains many of these same radioactive contaminants left over from atmospheric fallout from nuclear weapons testing from the 1950s to ’60s.

Take cesium-137 for example. The levels of radioactive contaminants are often reported in radioactivity units per volume, the units being Bq/m3 (one Becquerel is one decay event per second, and one cubic meter is about 260 gallons of water). In the ocean off the US West Coast, surface cesium levels are around 2 Bq/m3. This is the same as was measured off of San Onofre NPP in Dec. 2015, where the citizen scientist campaign, Our Radioactive Ocean, found a value of 1.9 Bq/m3.

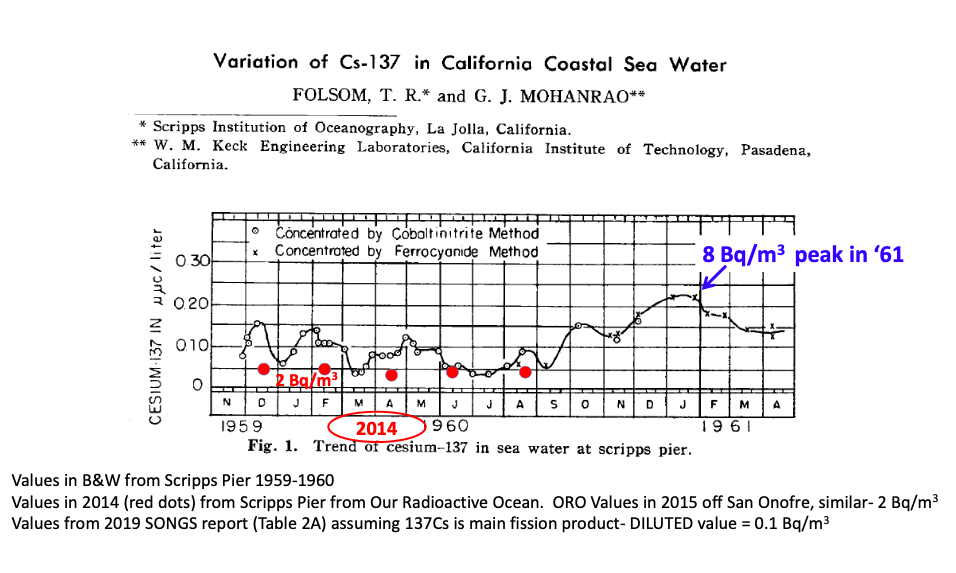

For background, the highest value recorded off the California coast was 8 Bg/m3 at Scripps Pier in La Jolla in 1961 (see datapoint in blue on below graph), when atmospheric fallout from nuclear missile testing was at its peak. By 2014, that level had declined to 2 Bq/m3 (data points in red on below graph).

Graphic provided by Dr. Ken Buesseler comparing 2014 cesium levels off of Scripps Pier to 1959-1960 levels. If we use the 2019 diluted cesium levels reported to be released as an indication of current release levels, it would mean a release 20 times lower than ambient cesium levels already in the area as of 2014.

The average level of fission products (cesium-137 being the main one) reported in the 2019 San Onofre effluent release report, is 0.06 to 0.1 Bq/m3 (Table 2A for fission products- original units are micro-Curies per milliliter). So the highest reported radioactive value in the liquid effluent release in 2019, is about 20 times lower than cesium-137 levels already in the ocean.

To put these levels in perspective of health effects: the reported dose (which is a measure of radiation health effects) received from swimming every day in the ocean off San Onofre for 100 years, would result in an additional dose that is more than 10 times smaller than the radiation we receive with a single dental x-ray. Not zero, but still very low.

That being said, different people have different levels of concern. More importantly, perhaps, is that assessment is based upon the average liquid effluent concentration numbers from the SONGS 2019 report after dilution. Is each release the same as the average? Is dilution constant? One could check to see if the radioactivity increases with release by sampling in the ocean near the known outfall site before, during, after announced releases. The easiest radioactive contaminant to monitor would be cesium-137, in part as it was the only fission product reported in most of the releases and is common from all nuclear power plants.

Ocean sampling for cesium-137 is available via OurRadioactiveOcean.org if a group of local citizen scientists want to help collect the 5 gallons needed to detect cesium-137 and crowd-fund to help pay for analyses at our research facility at WHOI. The ORO model and website provide more information on the cost ($550 per sample) and ease of collection (a 5 gallon sampling kit is available to be sent out and returned with prepaid shipping). The 2014 result in the ocean discussed above was analyzed as part of that program, but that sampling was not targeted to a particular release event. The sensitivity of the ORO analyses is more than 100 times higher than that used by SONGS, so even a small change to the local levels could be detected.

2. What would happen if you were to accidentally ingest one of these isotopes from swallowing beach water when surfing or recreating? What about if you were to ingest one of these isotopes from eating seafood near the discharge site?

Another way to look at this is by comparing the amount of isotopes released to established drinking water health standards. The levels of cesium-137 in the ocean today (2 Bq/m3) are about 5,000 times lower than the drinking water standard (10,000 Bq/m3; WHO standard for adult), indicating that ingesting a small or even large amount of ocean water should not be of concern.

Also, given the levels in the ocean today, we would not expect there to be a concern either for humans consuming seafood near the outfall or for the health of marine life near the outfall. For example, the level of cesium-137 in the ocean would need to be greater than 1000 Bq/m3, for the uptake in fish to cause cesium levels to exceed even the most stringent threshold set by Japan for consumption in seafood (100 Bq/kg). So we are far from this level in the ocean to need to be concerned about seafood consumption. In the last decade, only the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster resulted in radioactive contaminant levels in the ocean that required closing of local fisheries for several years.

3. How well do these isotopes dilute in the marine environment? Do they dissolve in saltwater and spread fairly evenly throughout the ocean, or could they collect in a certain area causing higher concentrations?

Most of these radioactive contaminants would be largely dissolved and become diluted as they are transported away from the release point, which is 1.1 miles offshore of San Onofre State Beach. Depending upon the chemical nature of the contaminant, some isotopes are more likely to be incorporated into marine life and seafloor sediments than others [you can learn more about this in Dr. Buesseler’s recent publication in Science, linked below]. However, at the levels being reported for the releases, we do not expect the amount of radioactivity that accumulates in seafood or the seafloor would lead to any measurable health effects in humans who swim or surf in the area.

4. The discharge is released 1.1 miles offshore, which is expected to provide ample dilution of these radioactive waters; yet, could currents in the area prevent this dilution or cause the discharge to get pushed closer to shore?

Currents and tides will change where the discharge water moves, but due to dilution, concentration in water always gets lower with distance. And while we didn’t detect any increase in local waters, that has only been tested once in the last several years and not specific to time/location of discharge. As mentioned, we could test this again if someone were to collect samples and send to ORO.

5. I think many are concerned about cumulative exposure, for instance if we get exposed to radiation from all these other sources, isn't that even more cause for concern of getting additional exposure through beach water?

Not necessarily. The cumulative exposure is still very small because the daily/annual exposure is small.

Want to learn more?

Surfrider plans to host a live webinar with Dr. Buesseler on this very topic in the coming months. Our hope is that this webinar will provide the chance to learn more and get your specific questions answered by a truly independent expert on the topic.

In the meantime, check out these useful links for additional information:

-

Our Radioactive Ocean: www.ourradioactiveocean.org/

-

Our Radioactive Ocean handout: www.ourradioactiveocean.org/2019-ORO-Brochure-Final-English.pdf

-

WHOI Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP and radioactivity FAQ site: www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/pollution/fukushima-radiation/faqs-radiation-from-fukushima/

-

Dr. Buesseler’s recent publication in Science: Opening the floodgates at Fukushima