By Katie Day and Miho Ligare

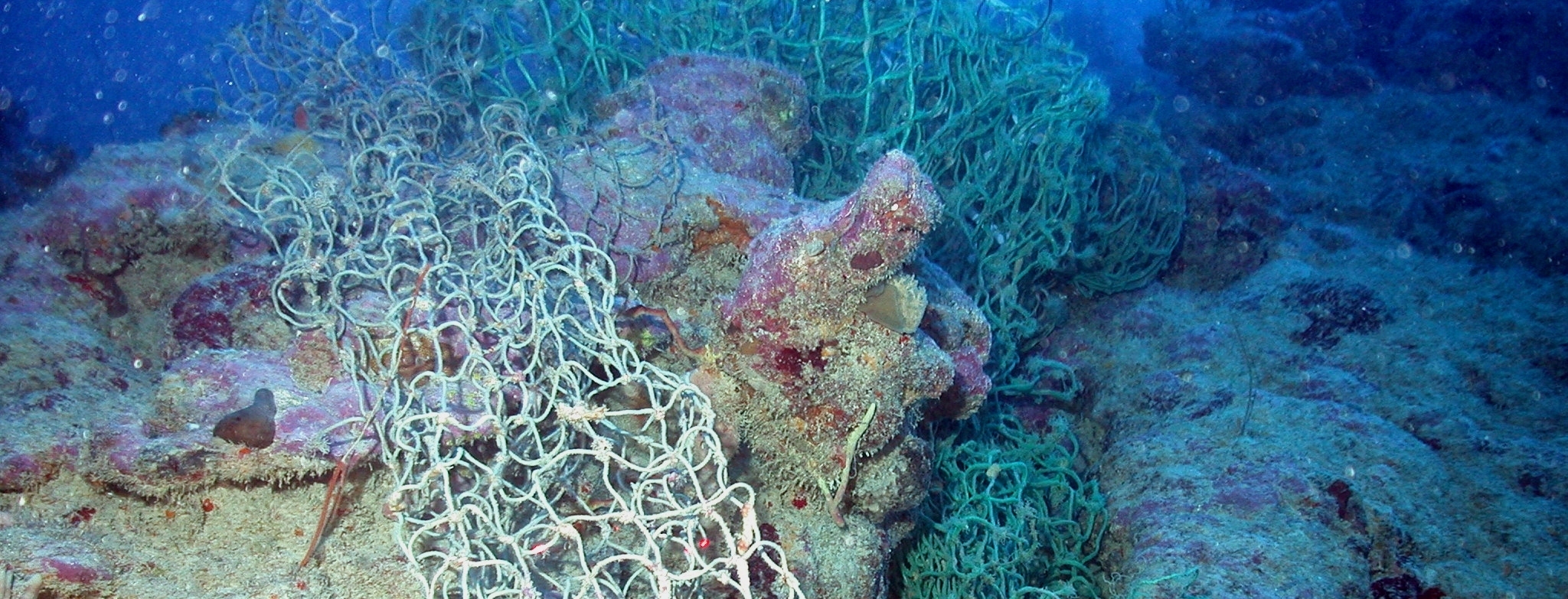

Derelict fishing gear or “ghost gear” refers to “nets, lines, crab/shrimp pots, and other recreational or commercial fishing equipment that has been lost, abandoned, or discarded in the marine environment.” Similar to single use plastic pollution, derelict fishing gear is harmful to our marine environment, and even though the amount that gets left in our ocean is estimated to be substantially less than land-based plastics, it can be even more dangerous to marine life. Let’s learn more about the problem of ghost gear, current research gaps, and organizations working on this issue.

1. In terms of ocean litter, derelict fishing gear poses the greatest direct ecological threat to marine animals.

Ghost fishing can occur when derelict fishing gear continues to trap and entangle marine animals. One study found that fishing-related items like buoys, rope, monofilament, and nets, were the litter items that caused the most damage to marine life due to entanglement. However, balloons and plastic bags had the highest risk of ingestion for certain marine life, including sea turtles, birds and marine mammals. Additionally, there are still a lot of unknowns about the effects of microplastics on marine animals, which are much more difficult to quantify.

Surfrider has been advocating for and supporting policies to reduce both ocean-based and land-based trash for many years. We have directly advocated on single-use plastic bags and prevented intentional releases of balloons for many years. Our chapters and volunteers have also removed thousands of derelict fishing nets from our coastal environment each year (roughly 15,000 nets removed in 2020 alone), along with hundreds of thousands of pieces of plastic pollution (for more information, read our 2019 Beach Cleanup Annual Report). We also value the work done by groups like the Global Ghost Gear Initiative as action to prevent and remove derelict fishing gear is also integral to the protection of our marine life.

2. Ocean gyres accumulate more ocean plastic

Due to ocean currents, wind, and salinity, gyres tend to be hotspots for floating plastic pollution. For example, a study showed that in the eastern part of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, commonly known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, 46% of the floating plastic mass consisted of fishing nets (by weight). This is in comparison to an estimate that ghost fishing gear makes up at least 10% of all marine litter.

3. There are still a lot of unknowns, and more research is necessary to fully understand the threats to our ocean

Despite the efforts of many, we still do not know the amount of derelict fishing gear that gets discarded in our ocean each year, or the cumulative amount that’s been dumped to date. While we have estimates of other marine litter, such as single-use plastics, that reach the ocean from land-based sources, most recently estimated at 11 million metric tons annually, the lack of data and tracking of the notably harmful, derelict fishing gear is concerning. Other types of marine plastics are also getting national attention, including microplastics.

For instance, the same study that showed more fishing gear in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre also showed that 94% of plastic items in the gyre were floating pieces of microplastic (by count). Microplastics are very small pieces of plastic created when plastic products degrade and break down overtime. Sources of microplastics can include car tires, single-use plastics, plastic-based clothing and even derelict fishing gear. We know that marine animals ingest these microplastics, mistaking them for food. One study found that “in controlled studies, chemicals have been shown to release from plastic after it is ingested by a variety of marine species,” meaning that whatever consumes the plastic could also absorb the chemicals from the material. These chemicals can be harmful to both the wildlife that consumes them, and to animals higher up in the food chain as some toxins are known to bioaccumulate. This means that the amount of toxins can increase as they work their way up the food chain, and eventually even reach humans. The impacts to marine life and humans from ingesting microplastics from a wide variety of sources, and their accompanied toxins and toxicants are still unknown, yet research is ongoing.

Finally, it's important to emphasize that there isn't a silver bullet when working in ocean conservation, and we need collaborative and diverse solutions to address this global issue. This could look like passing laws addressing single-use plastics and plastic production, conducting beach cleanups and derelict fishing gear cleanups, working with businesses to encourage more sustainable practices, and minimizing the use of single-use plastics through individual actions. The Surfrider Foundation is committed to protecting our ocean, and our chapters and volunteers are working tirelessly to implement these solutions. To learn more about important efforts by other organizations focused primarily on preventing derelict fishing gear, check the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. To learn more about plastic pollution’s harmful effects, go to our Beachapedia page here.

Header Image: Personnel of the NOAA Ship NANCY FOSTER, US Virgin Islands